Cocotb : Project setup tips & AXI verification

Using cocotb to test basic design and AXI interface

In the fast paced digital landscape, Cocotb is a testbench framework that allows blablabla…

If you are here you already know what cocotb is and don’t want a generic intro that looks like it was “written” using a LLM.

If you really don’t know cocotb, you can find resources here

But here are some points of information I still need to put some emphasis on :

- Cocotb is used to write testbenches

- Cocotb is not a simulator, but rather uses a already established simulator in the backend

- Cocotb is open-source and easy to use; unlike the old and rigid proprietary tools you can find out there.

This is great because you just write a tesbench in python (fast & “easy”) and then use whatever simulator you want, cocotb will handle the simulating part for you.

In this post’s examples, I’ll use Verilator and I will show you how to :

- Setup a nice project (HDL & testbenches).

- Write basic testbenches

- Use cocotbext-axi to verify more complex interfaces without too much of a struggle (through a real example).

Pre-requisites

- Use linux (You can use windows but good luck with that)

- Knowledge of

- HDL (SystemVerilog)

- Python

- Basic Makefile

- Install cocotb

- Install a compatible verilator verision

- For AXI interface : Install the corresponding cocotb extension

- Have a wave visualizer to open the dumped waveforms (in

.vcdformat), I use GTKWave.

My personal tips for a good basic project setup

Note that the following setup is something I came up with myself and is NOT standard by any mean. But it works and I find it quite nice.

When starting an HDL project, you first want to create some HDL files, let’s do exactly that in a src folder :

.

├── src

│ └── logic1.sv

We’ll write very basic logic here :

module logic1 (

input logic clk,

input logic reset_n,

input logic data_in,

output logic data_out

);

always @(posedge clk) begin

if(~reset_n) begin

data_out <= 1'b0;

end else begin

data_out <= data_in;

end

end

endmodule

And now comes the time to test it. To do so we add a tb folder :

.

├── src

│ └── logic1.sv

├── tb

│ └── logic1

│ ├── Makefile

| └── test_logic1.py

Cocotb works by :

- Writing the tb in python (we’ll se that in a minute)

- Writing a Makefile to tell cocotb how to operate these tests by giving it

- some source files

- a similator (we’ll use Verilator)

- and other directives …

You can find guidilines for the Makefile here. In our case, here is the one I wrote :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

# Makefile

# defaults

SIM ?= verilator

TOPLEVEL_LANG ?= verilog

EXTRA_ARGS += --trace --trace-structs

WAVES = 1

VERILOG_SOURCES += $(PWD)/../../src/logic1.sv

# use VHDL_SOURCES for VHDL files

# TOPLEVEL is the name of the toplevel module in your Verilog or VHDL file

TOPLEVEL = logic1

# MODULE is the basename of the Python test file

MODULE = test_logic1

# include cocotb's make rules to take care of the simulator setup

include $(shell cocotb-config --makefiles)/Makefile.sim

Most of these are pretty self-explanatory. the EXTRA_ARGS += --trace --trace-structs line allows us to get waveforms for Verilator. And WAVE = 1 is for icarus verilog (I also used it so I keep that line here for good measure, you can delete it if you want).

Once this is done, all that remains to do is to run make in the tb/logic1 folder to test this module’s logic ! But for that we have to write a testbench of course !

You can also add as many HDL files for modules as you want and as many sub-folders in tb/ as you want to test them out !

Writing a basic testbench

When it come to the tesbench, the cocotb docs gives us many clues on how to do it and you don’t need that much feature after all do write some nice and robust testbenches.

Let’s review what makes a good testbench :

- Assertion

- Possibility of using a clock

- Maybe some randomness ?

So yeah you don’t need that much ! If you are here, there is a good chance you know how to make a testbench and maybe you know your way around cocotb.

Nevertheless, here is an example of how to make a basic testbench, with a clock signl, some randomness and a reset co-routine you can call whenever you need to reset the design.

Note that “

dut” stands for “Design Under Test” and is an handle you can use to access… well… all the dut’s signals to do whatever you want with it !

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

# test_logic1.py

import cocotb

from cocotb.clock import Clock

from cocotb.triggers import RisingEdge, Timer

import random

@cocotb.coroutine

async def reset(dut):

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

dut.reset_n.value = 0

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

dut.reset_n.value = 1

await Timer(1, units="ns")

print("reset done !")

assert dut.data_out.value == 0b0

@cocotb.test()

async def initial_read_test(dut):

cocotb.start_soon(Clock(dut.clk, 1, units="ns").start())

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

# call the reset co-routine

await reset(dut)

# do some random tests

N_TESTS = 1000

for _ in range (N_TESTS):

test_value = random.randint(0, 1)

dut.data_in.value = test_value

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

assert dut.data_out == test_value

And now, with our test set up, all that remains to do is to run the make command in our tb sub-dir and we’re all set !

In the backend, Verilator will run and create some build_dir with all of the compiled files that we don’t care about because cocotb handles this for us.

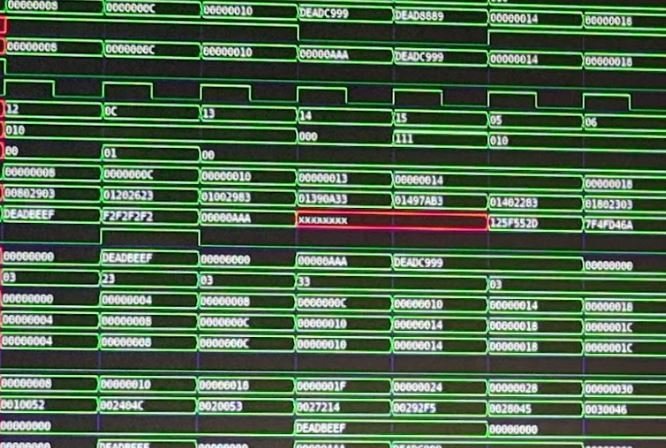

Given that we wrote our makefile the right way, we now have a dump.vcd file that contains all the waveforms. You can open it using gtkwave dump.vcd or any other wave viewer you want :

This waveform is totally unrelated to the design we just made, It’s just an illustration.

A tip to have a clean workspace

Running the test can create a lot of build folders and files. I suggeest you use a makefile at the root of your project with the only purpose of cleaning the project.

Here is an example of such a Makefile from the HOLY CORE course I’m developing right now :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

.PHONY: clean

clean:

@find ./tb -type d -name "__pycache__" -exec rm -rf {} +

@find ./tb -type d -name "sim_build" -exec rm -rf {} +

@find ./tb -type f -name "results.xml" -exec rm -f {} +

@find ./tb -type f -name "*.None" -exec rm -f {} +

@find ./tb -type d -name ".pytest_cache" -exec rm -rf {} +

@find ./tb -type f -name "dump.vcd" -exec rm -f {} +

Another tip for when the project gets bigger

Imagine the following project where we have multiple designs to test (there are only 2 in this example but it could be a gazillion if you want) :

.

├── src

│ ├── logic1.sv

│ └── logic2.sv

├── tb

│ ├── logic1/

│ ├── logic2/

│ └── test_runner.py

The thing is when we design a specific module, we test it individually and we’re all happy with our testbench but sometimes (actually all the time) you want to run all tests to check on the whole project, and doing a cd in all of the testbench file individually is a pain.

To address this problem, we can leverage a test_runner that we can simply execute as a regular python file or use by running pytest in the tb/ folder.

Here are some resources the build you own test runner

And here is a test_runner example you can use for the project mentioned above :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

# test_runner.py

import os

from pathlib import Path

from cocotb.runner import get_runner

def generic_tb_runner(design_name):

sim = os.getenv("SIM", "verilator")

proj_path = Path(__name__).resolve().parent.parent

sources = list(proj_path.glob("src/*.sv"))

runner = get_runner(sim)

runner.build(

sources=sources,

hdl_toplevel=f"{design_name}",

build_dir=f"./{design_name}/sim_build",

build_args=[] # use this to add args for verilator

)

runner.test(hdl_toplevel=f"{design_name}", test_module=f"test_{design_name}", test_dir=f"./{design_name}")

def test_logic1():

generic_tb_runner("logic1")

def test_logic2():

generic_tb_runner("logic2")

if __name__ == "__main__":

test_logic1()

test_logic2()

As you can see, I personally like to standardize the names of my file wich allows me to use the test_runner like I did in this example. You can tweak this file to you need.

Leveraging cocotb extension to test AXI interface

And now the technical stuff. When designing an AXI interface for a system, there are a lot of things going on and even though the interface standards are not that hard to understand, It can be challenging to get it 100% right whilst complying with both our system requirements and the AXI standards (that’s why we test it after all).

Anyway, to verify our design, we can do assertions on the axi signals but what about what is next ? AXI is meant to work with multiple systems, meaning if we design an AXI master, we also need to design a slave to interact with it (and we also need to verify the slave) !

So it’s better to just use someone’s else works ! And to get a generic slave interface that was already verified to be compliant with the AXI standards, we can use cocotbext-axi

To install it, it’s pretty straight forward :

1

pip install cocotbext-axi

Then, we’ll imagine we want to design some memory module that gets data from RAM using AXI. What I suggest you do before diving into the actual testbench, is to add a test environment that is suitable for use with cocotbext-axi :

.

├── src

│ └── logic_axi.sv

├── tb

│ └── logic_axi

│ ├── Makefile

│ ├── axi_translator.sv

| └── test_logic_axi.py

Here I called it axi_translator.sv.

But why such a file ?

When we’ll declare our AxiRam slave from cocotbext-axi to verify our design’s compliance with AXI, we’ll need very specific names for the axi signals (with a constant prefix like axi_ and standard namings for the signals)

So rather than modifying everything in the tested module, just add it in an axi_translator top module that will serve as a “demux” (if you use system verilog interface) and a renamer, Here is an example using system verilog interface, you can also just use plain verilog and just rename the signals :

// This module instantiates the cache and routes the AXI interface as discrete Verilog signals for cocotb

module axi_translator (

// Clock and Reset

input logic clk,

input logic rst_n,

// Write Address Channel

output logic [3:0] axi_awid,

output logic [31:0] axi_awaddr,

output logic [7:0] axi_awlen,

output logic [2:0] axi_awsize,

output logic [1:0] axi_awburst,

output logic axi_awvalid,

input logic axi_awready,

// Write Data Channel

output logic [31:0] axi_wdata,

output logic [3:0] axi_wstrb,

output logic axi_wlast,

output logic axi_wvalid,

input logic axi_wready,

// Write Response Channel

input logic [3:0] axi_bid,

input logic [1:0] axi_bresp,

input logic axi_bvalid,

output logic axi_bready,

// Read Address Channel

output logic [3:0] axi_arid,

output logic [31:0] axi_araddr,

output logic [7:0] axi_arlen,

output logic [2:0] axi_arsize,

output logic [1:0] axi_arburst,

output logic axi_arvalid,

input logic axi_arready,

// Read Data Channel

input logic [3:0] axi_rid,

input logic [31:0] axi_rdata,

input logic [1:0] axi_rresp,

input logic axi_rlast,

input logic axi_rvalid,

output logic axi_rready,

);

// Declare the AXI master interface for the cache

axi_if axi_master_intf();

// Connect the discrete AXI signals to the axi_master_intf

assign axi_master_intf.aclk = clk;

assign axi_master_intf.aresetn = rst_n;

// Write Address Channel

assign axi_awid = axi_master_intf.awid;

assign axi_awaddr = axi_master_intf.awaddr;

assign axi_awlen = axi_master_intf.awlen;

assign axi_awsize = axi_master_intf.awsize;

assign axi_awburst = axi_master_intf.awburst;

assign axi_awvalid = axi_master_intf.awvalid;

assign axi_master_intf.awready = axi_awready;

// Write Data Channel

assign axi_wdata = axi_master_intf.wdata;

assign axi_wstrb = axi_master_intf.wstrb;

assign axi_wlast = axi_master_intf.wlast;

assign axi_wvalid = axi_master_intf.wvalid;

assign axi_master_intf.wready = axi_wready;

// Write Response Channel

assign axi_master_intf.bid = axi_bid;

assign axi_master_intf.bresp = axi_bresp;

assign axi_master_intf.bvalid = axi_bvalid;

assign axi_bready = axi_master_intf.bready;

// Read Address Channel

assign axi_arid = axi_master_intf.arid;

assign axi_araddr = axi_master_intf.araddr;

assign axi_arlen = axi_master_intf.arlen;

assign axi_arsize = axi_master_intf.arsize;

assign axi_arburst = axi_master_intf.arburst;

assign axi_arvalid = axi_master_intf.arvalid;

assign axi_master_intf.arready = axi_arready;

// Read Data Channel

assign axi_master_intf.rid = axi_rid;

assign axi_master_intf.rdata = axi_rdata;

assign axi_master_intf.rresp = axi_rresp;

assign axi_master_intf.rlast = axi_rlast;

assign axi_master_intf.rvalid = axi_rvalid;

assign axi_rready = axi_master_intf.rready;

// Instantiate the cache module

logic_axi #(

) cache_system (

.clk(clk),

.rst_n(rst_n),

// AXI Master Interface

.axi(axi_master_intf)

);

endmodule

Making it by hand is a tidious process, this kind of work can be done by an LLM but they still tend to make lots of mistakes in SystemVerilog, Be advised !

And with our new axi_translator as a the top-level dut, we can use the cocotbext-axi’s AxiRam to simulate some RAM we’ll try to access.

The cocotbext-axi is pretty easy to use once you get your head around how it works, especially given the ease of use of python :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# test_logic_axi.py

import cocotb

from cocotb.clock import Clock

from cocotb.triggers import RisingEdge, Timer

import random

from cocotbext.axi import AxiBus, AxiRam

@cocotb.test()

async def example_test(dut):

SIZE = 4096 # 12 bits / 3 bytes addressable

axi_ram_slave = AxiRam(AxiBus.from_prefix(dut, "axi"), dut.clk, dut.rst_n, size=SIZE, reset_active_level=False)

Once this is done, You can tinker around with your logic and initalize a read request for example :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

@cocotb.test()

async def example_test(dut):

SIZE = 4096 # 12 bits / 3 bytes addressable

axi_ram_slave = AxiRam(AxiBus.from_prefix(dut, "axi"), dut.clk, dut.rst_n, size=SIZE, reset_active_level=False)

# Init a read request (pseudo code for example)

dut.logic_axi.next_state_in.value = SEND_READ_REQUEST

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

await Timer(1, units="ps")

# Check that the signals are okay

assert dut.axi_arvalid.value == 0b1 # The address read request is valid

# other checks ...

And the great thing afterwards is that , after you do all your necessary checks, and advance in the clock cycle, the AxiRam Will actually react and send the responses !

So we can further improve our testing by waiting for a arready flag on the address_read channel from the AxiRam as the AxiRam acts separately, just like a real RAM controller would.

Here is a more in-depth example from a bigger project of mine you can use as a more extensive inspiration :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

# tb_exmple.py

# ...

@cocotb.test()

async def initial_read_test(dut):

# ...

axi_ram_slave = AxiRam(AxiBus.from_prefix(dut, "axi"), dut.clk, dut.rst_n, size=SIZE, reset_active_level=False)

# ...

# Wait

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

await Timer(1, units="ps")

# new state should be waiting for read data to arrive

assert dut.cache_system.state.value == RECEIVING_READ_DATA

# Check the corresponding axi signals

assert dut.axi_arvalid.value == 0b0

assert dut.axi_rready.value == 0b1 # the cache is ready to get its data !

i = 0

while( (not dut.axi_rvalid.value == 1) and (not i > DEADLOCK_THRESHOLD)) :

# if the data is not readable yet, we wait the next clock cycle

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

await Timer(1, units="ps")

# if we are here, it is because we just passed an AXI clock edge where the read data is valid

# that means the cpu will start reading the next 128 words and then go to IDLE

# and return the data to the CPU.

i = 0

while( i < CACHE_SIZE - 1) :

# Check if the handshake is okay

if((dut.axi_rvalid.value == 1) and (dut.axi_rready.value == 1)) :

# a word is sent to cache and is store in the cache block

assert dut.cache_system.write_set.value == i

i += 1

# goto next clock cycle, last flag is never high

assert dut.axi_rlast.value == 0b0

assert dut.cache_system.cache_stall.value == 0b1 # make sure stall is always HIGH

await RisingEdge(dut.clk)

await Timer(1, units="ps")

# ...

Outro

I will not insult you with some meaningless LLM generated outro to “open the subject”.

That’s all there is to it.

You can leave a comment below if you have any question or contact me directly.